Including demographic processes in a population model

Jian Yen

07/01/2026

Source:vignettes/including_processes.Rmd

including_processes.RmdDemographic processes?

This is a broad term that could mean many things.

aae.pop focuses on five main processes:

demographic stochasticity: random variation in the outcomes of individual processes (e.g. birth, death), resulting in variation in population abundances.

environmental stochasticity: random variation in external conditions, resulting in variation in the vital rates (i.e., the population matrix).

density dependence: variation in vital rates or population outcomes that depends on the abundance of the population. Density dependence can be negative (e.g., due to limited resources) or positive (e.g., Allee effects).

covariate effects: the influence of covariates on the population matrix. In

aae.pop, covariate effects are included primarily to allow the population matrix to change through time in response to external factors (e.g., weather, habitat availability, management interventions).additions or removals: any processes that lead to individuals being added to or removed from a population. Additions and removals are defined broadly but can capture things like population augmentation (e.g., stocking or releases of captive-bred individuals) and targeted removals (e.g., angling or predation).

Two additional processes, dispersal and interspecific interactions, are covered in the Metapopulations and Multiple species vignettes.

An aside: masks

The processes above are unlikely to have consistent effects across

all vital rates or all classes in a population. To deal with this,

aae.pop is built around a concept of masks. Masks

are used to select specific elements of the population matrix, and only

these elements are altered by a given process.

Masks are paired with functions when defining all of the above processes. Masks tell R which cells to target, functions tell R what to do to these cells.

Several helper functions are included to define common masks. These

include the reproduction, survival, and

transition regions of the matrix discussed in the getting started vignette, as well as masks

to select an entire population matrix (all_cells) or

abundance vector (all_classes).

The masks defined in aae.pop return a

TRUE/FALSE matrix or vector that selects the

required cells. Masks are defined in this way because

aae.pop flattens the population matrix in all internal

calculations, which breaks cell-based subsetting (i.e., the

[i, j] R notation will not work). It is possible (but not

advised) to work around this. The discussion below

introduces one way to work around masks and highlights why this might

not be a good idea.

Back to demographic processes

A basic model

Let’s start with the basic model used in the Getting started vignette. This was a Leslie matrix with five age classes, with individuals reproducing from ages 3-5.

popmat <- rbind(

c(0, 0, 2, 4, 7), # reproduction from 3-5 year olds

c(0.25, 0, 0, 0, 0), # survival from age 1 to 2

c(0, 0.45, 0, 0, 0), # survival from age 2 to 3

c(0, 0, 0.70, 0, 0), # survival from age 3 to 4

c(0, 0, 0, 0.85, 0) # survival from age 4 to 5

)This is sufficient to start simulating population dynamics, using the

dynamics and simulate functions. However,

adding additional processes requires a few more steps first.

Demographic stochasticity

Random variation in individual outcomes is a key feature of most population models. This variation is most important (and influential) when populations are small, so that a few small events (e.g., several individuals failing to reproduce) can have a big effect on population outcomes.

Demographic stochasticity will be defined here with a single

mask and its corresponding function. The

simplest form of demographic stochasticity in this case is Poisson

variation around the expected number of individuals in the next

generation. This can be coded as:

demostoch_mask <- all_classes(popmat) # affects all classes

demostoch_fn <- function(x) {

rpois(length(x), lambda = x)

}Here, the mask selects all classes in the population

vector and the function takes this vector x

and returns random Poisson variates with mean equal to x.

Note that this function potentially allows the number of surviving

individuals in a class to exceed the number of available individuals

because the Poisson distribution does not have an upper bound. A

workaround for this, using the Binomial distribution, is covered in the

Beyond defaults vignette.

The mask/function pair can be combined into

a single object with the demographic_stochasticity

function.

demostoch <- demographic_stochasticity(

masks = demostoch_mask,

funs = demostoch_fn

)The resulting demostoch object can be passed directly to

dynamics, along with the population matrix. In turn, this

creates a dynamics object that can be used in

simulate.

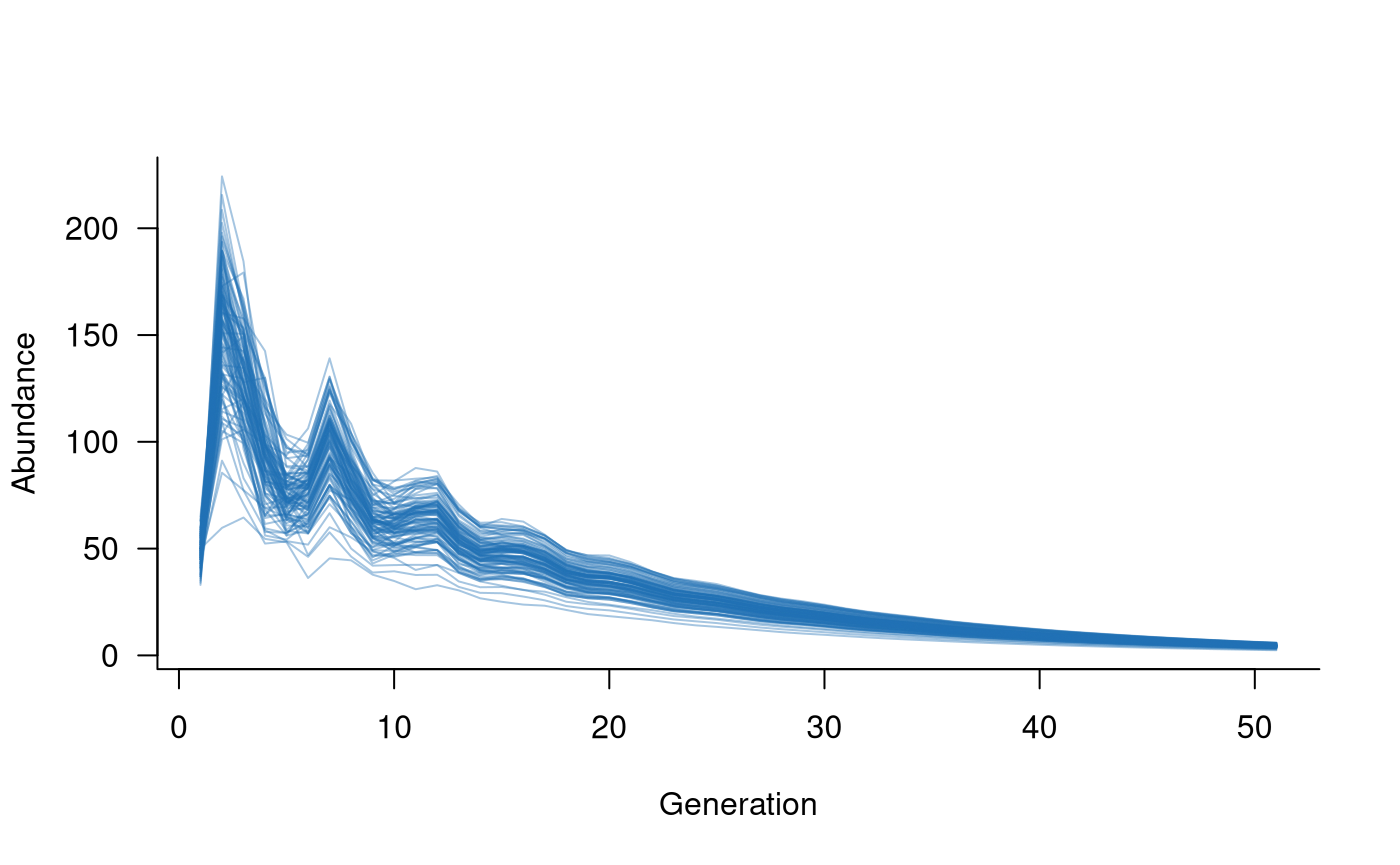

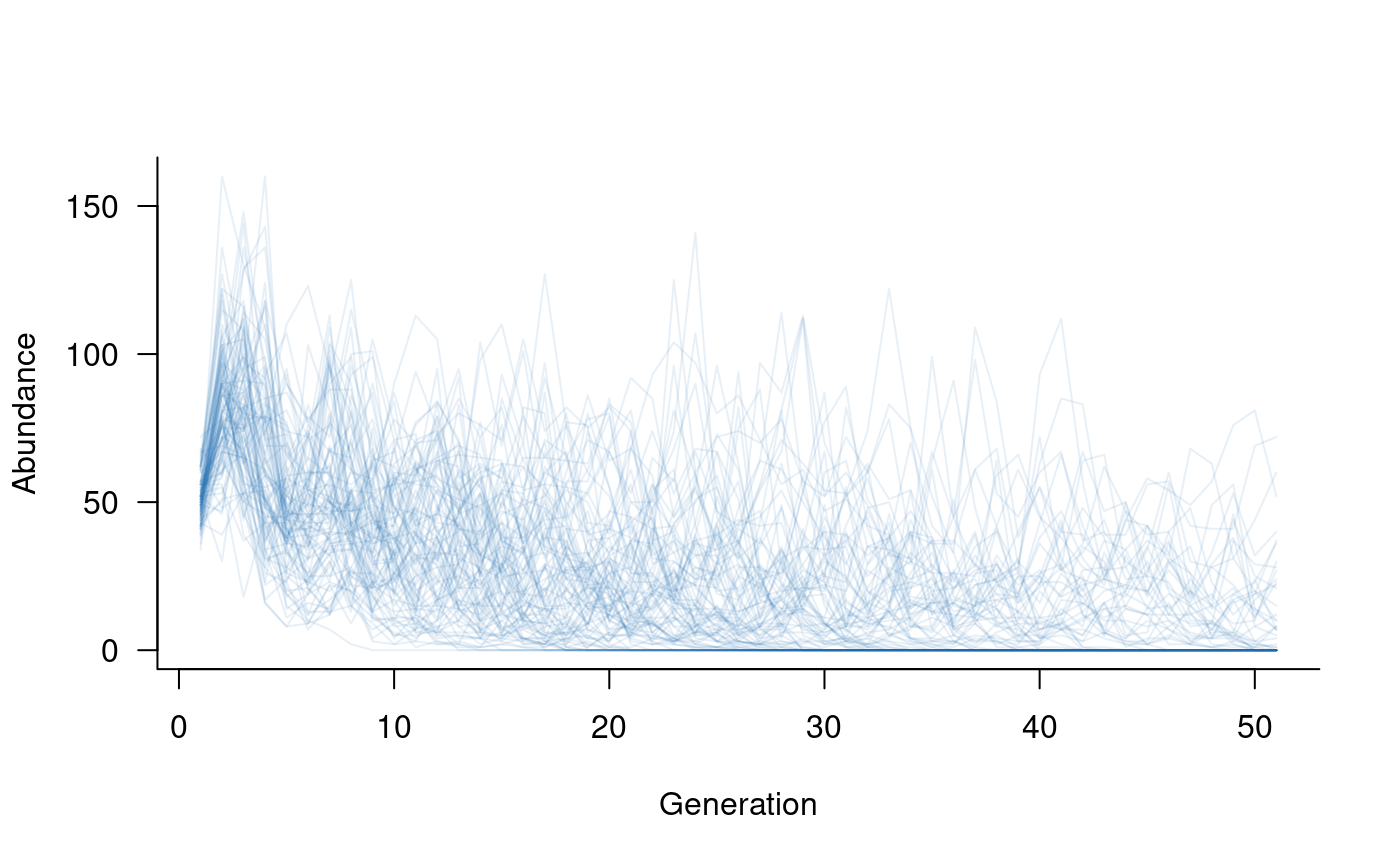

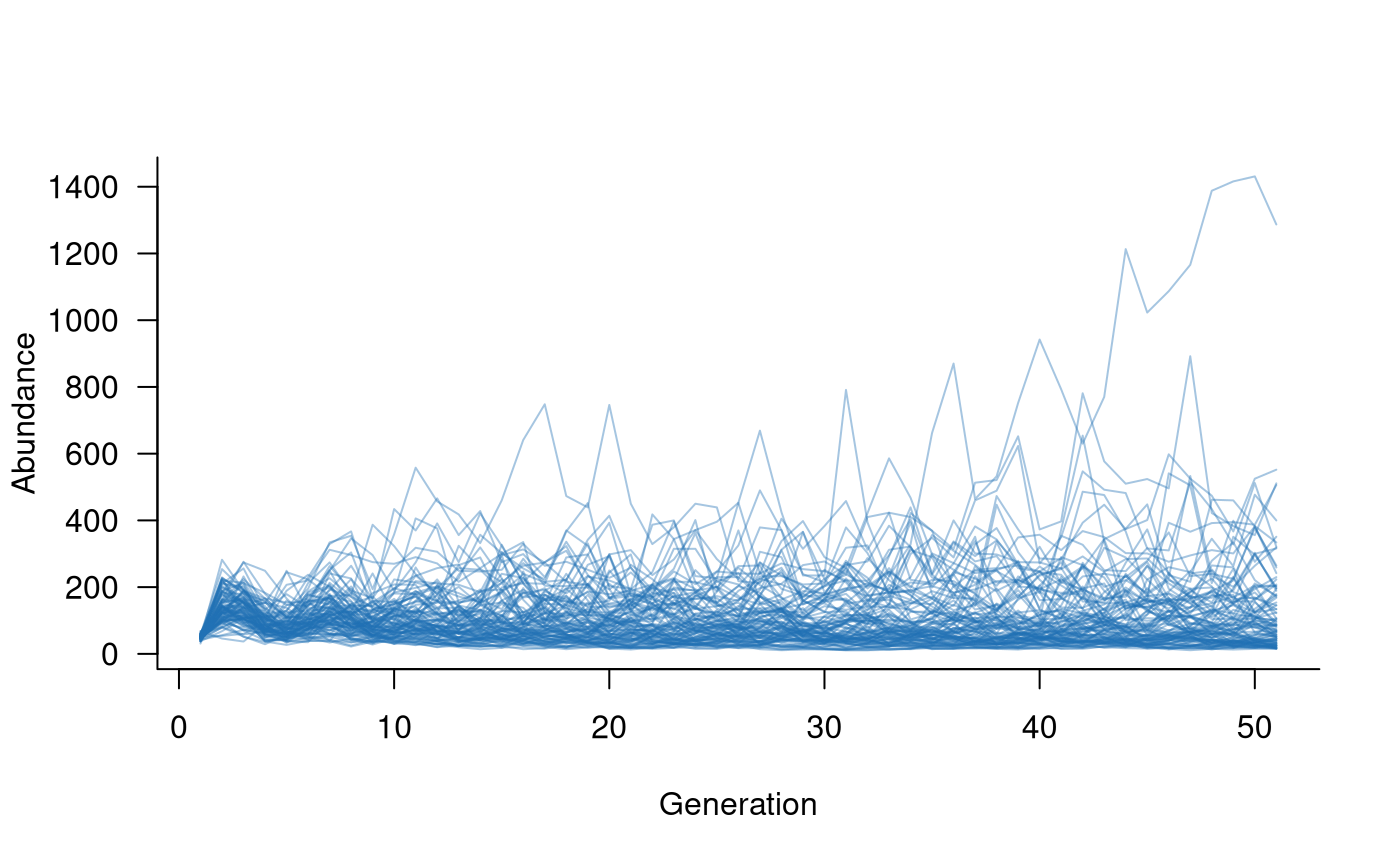

# create population dynamics object

popdyn <- dynamics(popmat, demostoch)

# simulate population dynamics

sims <- simulate(popdyn, nsim = 100)

# plot the population trajectories

plot(sims, col = alpha("#2171B5", 0.4))

This simple example includes one mask/function pair, but the

demographic_stochasticity function can chain together as

many different mask/function pairs as required. In these cases, there

should be one mask for each function, and the set of masks/functions

should be passed to demographic_stochasiticity as a list

(e.g., masks = list(demostoch_mask1, demostoch_mask2)).

Environmental Stochasticity

Environmental stochasticity will be defined here with two masks and their corresponding functions. The simplest form of variation in reproduction is Poisson variation around the expected number of new individuals. This can be coded as:

reproduction_mask <- reproduction(popmat, dims = 3:5) # only ages 3-5 reproduce

reproduction_fn <- function(x) {

rpois(length(x), lambda = x)

}Here, the mask selects the reproductive output of age

classes 3 to 5 in the population matrix and the function

takes this vector x and returns random Poisson variates

with mean equal to x.

The second mask/function pair will add

variation in survival outcomes. In this case, a simple form of variation

is to add or subtract some small value from the survival probabilities.

This can be coded up as:

transition_mask <- transition(popmat) # all classes this time

transition_fn <- function(x) {

# add a random deviation to x

deviation <- runif(length(x), min = -0.1, max = 0.1)

x <- x + deviation

# make sure the result isn't negative or greater than 1

x[x < 0] <- 0

x[x > 1] <- 1

# return the value

x

}Here, the mask selects all elements on the sub-diagonal

of the population matrix, and the function takes some

vector x and returns a new value with a deviation between

-0.1 and 0.1. There is one extra check in the function to make sure that

the new probabilities are still probabilities (i.e., still between 0 and

1).

These two mask/function pairs can be

combined into a single object with the

environmental_stochasticity function.

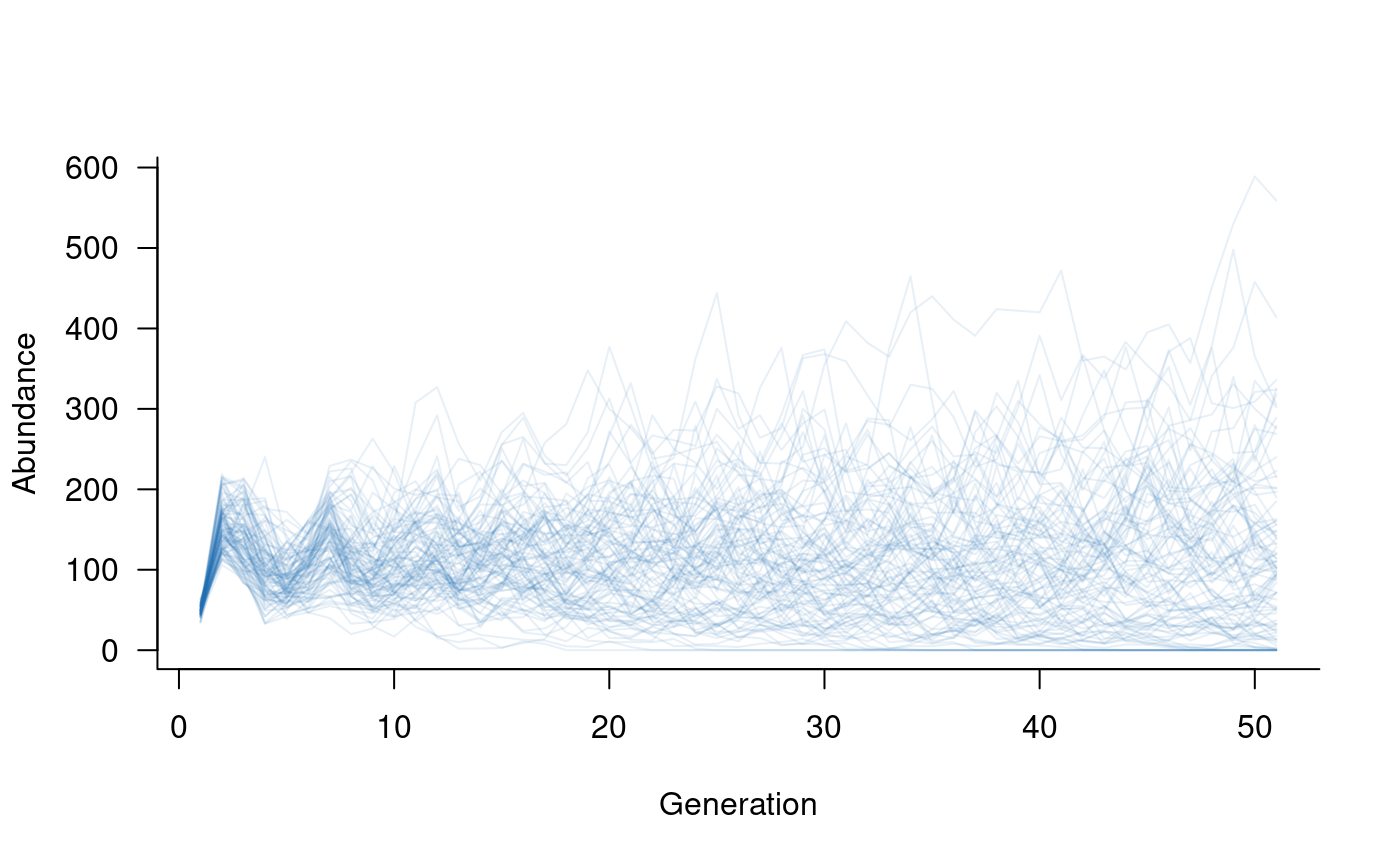

envstoch <- environmental_stochasticity(

masks = list(reproduction_mask, transition_mask),

funs = list(reproduction_fn, transition_fn)

)The resulting envstoch object can be passed directly to

dynamics, along with the population matrix. In turn, this

creates a dynamics object that can be used in

simulate.

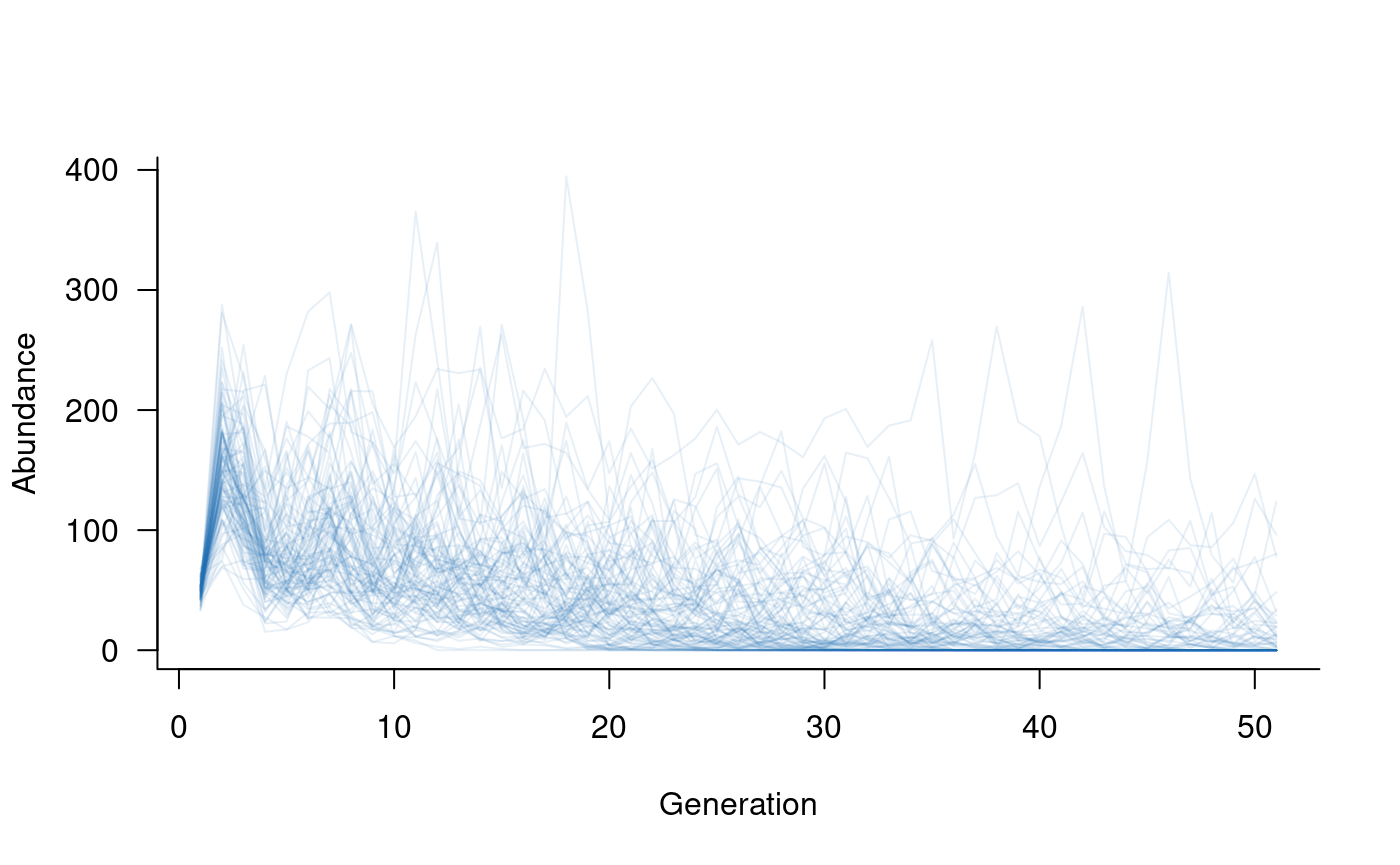

# create population dynamics object

popdyn <- dynamics(popmat, envstoch)

# simulate population dynamics

sims <- simulate(popdyn, nsim = 100)

# plot the population trajectories

plot(sims, col = alpha("#2171B5", 0.4))

It is easy to include both environmental and demographic

stochasticity in the same model. The dynamics call simply

needs both envstoch and demostoch objects.

This is a case where the update function comes in handy.

Rather than re-defining the population dynamics object, the existing

version of popdyn (which included popmat and

envstoch) can simply be updated to include

demostoch:

# update population dynamics object

popdyn <- update(popdyn, demostoch)

# simulate population dynamics

sims <- simulate(popdyn, nsim = 100)

# plot the population trajectories

plot(sims, col = alpha("#2171B5", 0.4))

Density dependence

Density dependence occurs when vital rates or individual outcomes depend on population abundance. The most common form of density dependence in population ecology is negative density dependence, that is, a reduction in vital rates with increases in population abundance. Negative density dependence is typically observed as changes in reproduction due to, for example, increased competition for resources resulting in high mortality of new individuals.

Density dependence can be included in exactly the same way as

environmental stochasticity: a mask tells R which cells in

the population matrix are affected by abundances and a

function tells R what to do with these cells. In this case,

the function is passed the vital rates as well as the

vector of abundances in each population class.

aae.pop has pre-defined functions for two common forms

of density dependence: the Ricker model and the

Beverton-Holt model. The Ricker model assumes that mortality

rates of new individuals are proportional to adult population size due

to scramble competition (equal division of resources). The

Beverton-Holt model assumes that mortality rates of new individuals are

linearly dependent on the number of individuals due to contest

competition (unequal division of resources). Importantly, the

Ricker model is overcompensatory, which means it can increase

mortality rates to the point of complete mortality. This does not occur

under the Beverton-Holt model.

In aae.pop, both models are specified with two

parameters: k, that represents the carrying

capacity of the population; and theta, which

represents the strength of density dependence. theta

re-scales population sizes, so is mathematically equivalent to adjusting

k (e.g., theta = 0.5; k = k and

theta = 1; k = 2 * k will give the same outcome). Both

functions include one extra argument, exclude, which allows

estimates of carrying capacity to be defined for a subset of population

classes (e.g., adult abundances only). A Ricker model can be specified

as follows:

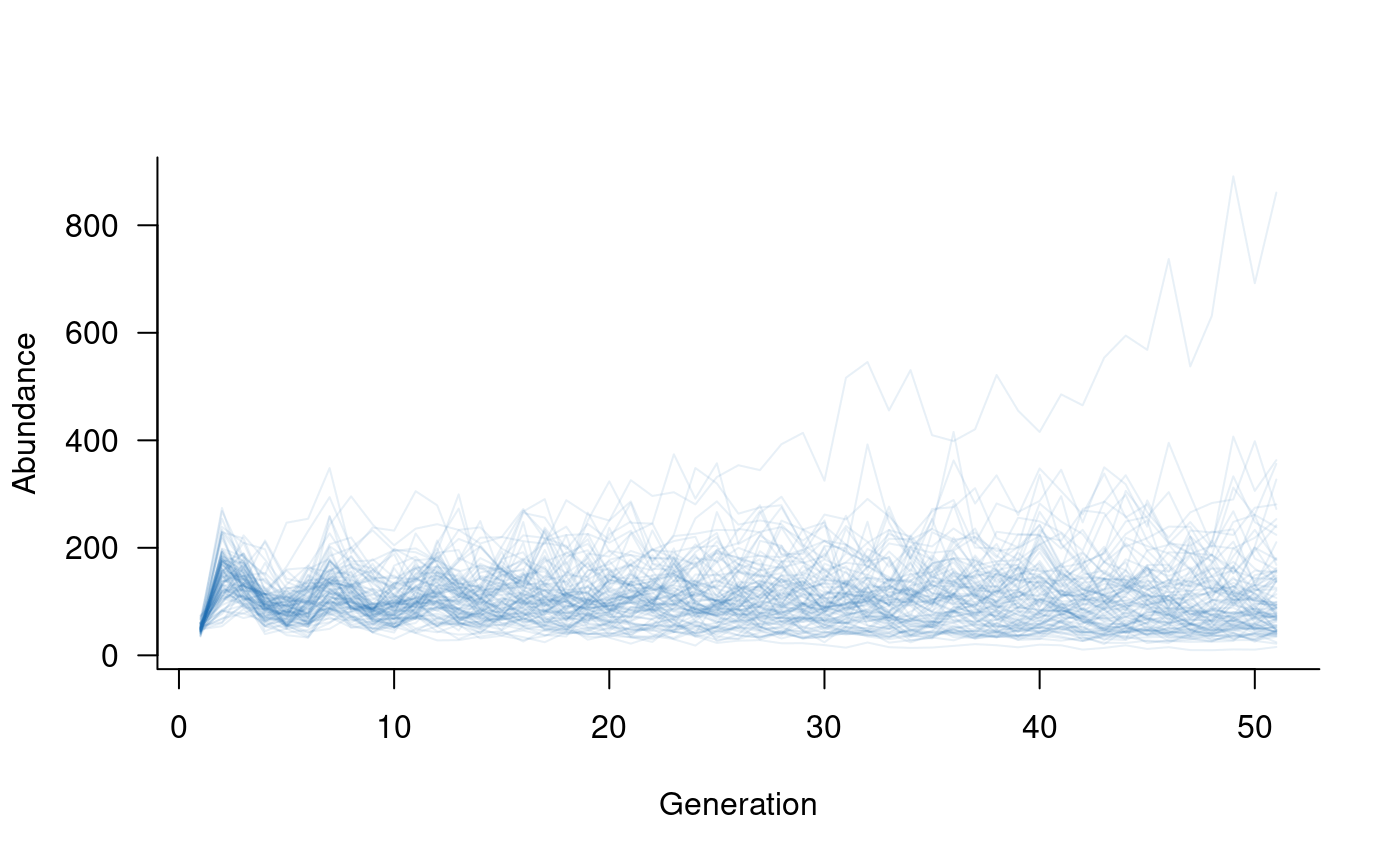

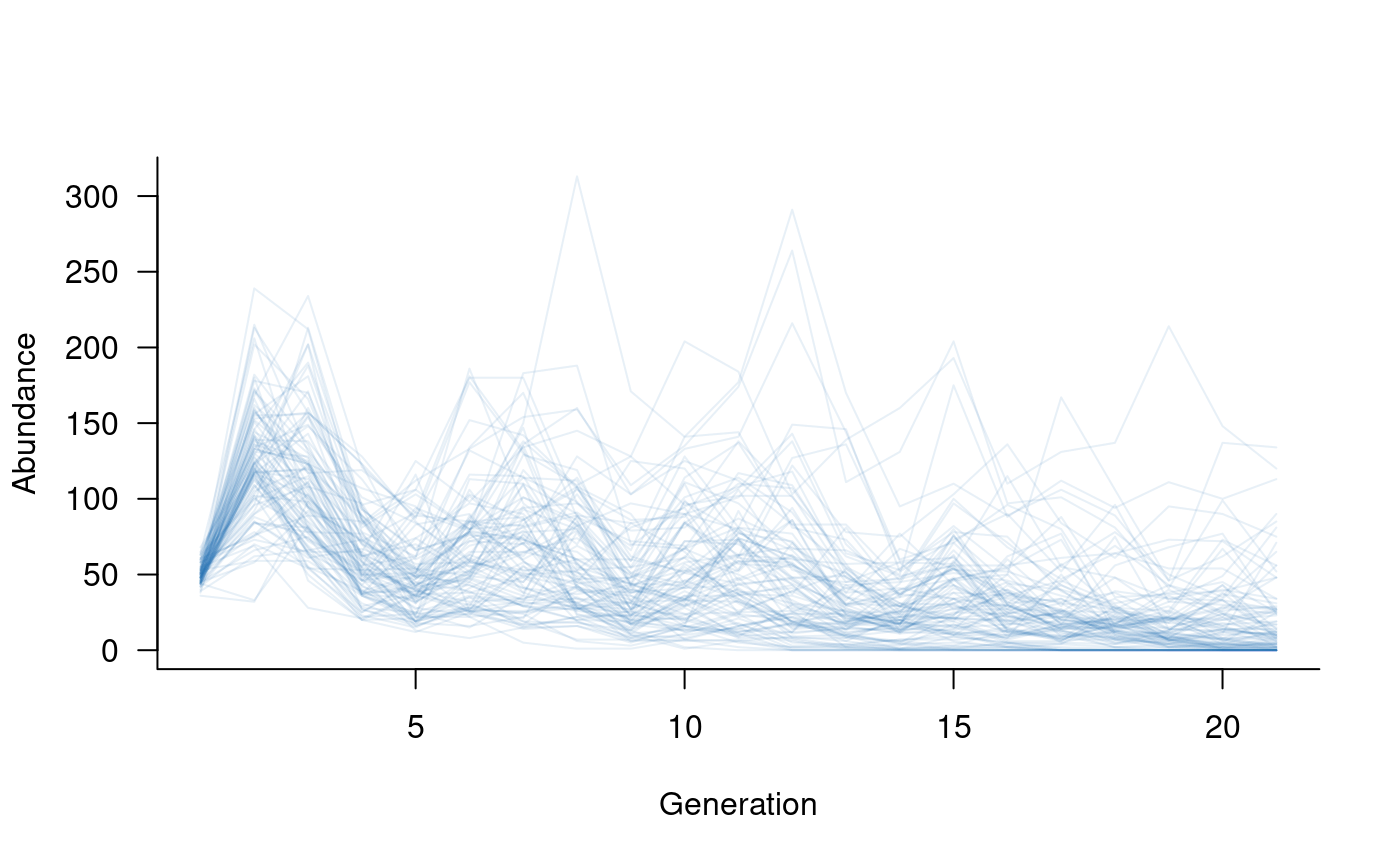

# specify a Ricker model for density dependence

dd <- density_dependence(

masks = reproduction(popmat, dims = 3:5), # only adults reproduce

funs = ricker(k = 40, exclude = 1:2) # set k based on adult abundances

)

# update the population dynamics object to include density dependence

popdyn <- update(popdyn, dd)

# simulate population dynamics

sims <- simulate(popdyn, nsim = 100)

# plot the population trajectories

plot(sims, col = alpha("#2171B5", 0.4))

Density dependence can take many other forms. These forms may include positive density dependence (e.g., Allee effects) or may affect adult abundances as well as reproduction. The next section introduces an example of the latter.

A different form of density dependence

Density dependence is most commonly assumed to affect only the new

individuals entering the population. However, it is possible that

density dependence also affects adults, for example, when high

abundances limit access to suitable habitat. Effects on adult survival

could be modelled using the approach outlined in the previous section,

with transition or survival masks alongside

the reproduction mask.

An alternative approach is to model density dependence through its direct effects on population abundances. Although not linked directly to vital rates (e.g., survival), this approach can be easier to implement and can capture processes that do not directly affect vital rates, such as fishing, hunting, or logging.

The add_remove_pre and add_remove_post

functions can be used to define this form of density dependence

(_pre: before reproduction; _post: after

reproduction). These functions are described in more detail below and

replace the now-deprecated density_dependence_n function.

In this case, the mask needs to select the relevant classes

in the population, and the function takes only one

argument, the vector of population abundances. This approach can be

implemented as follows:

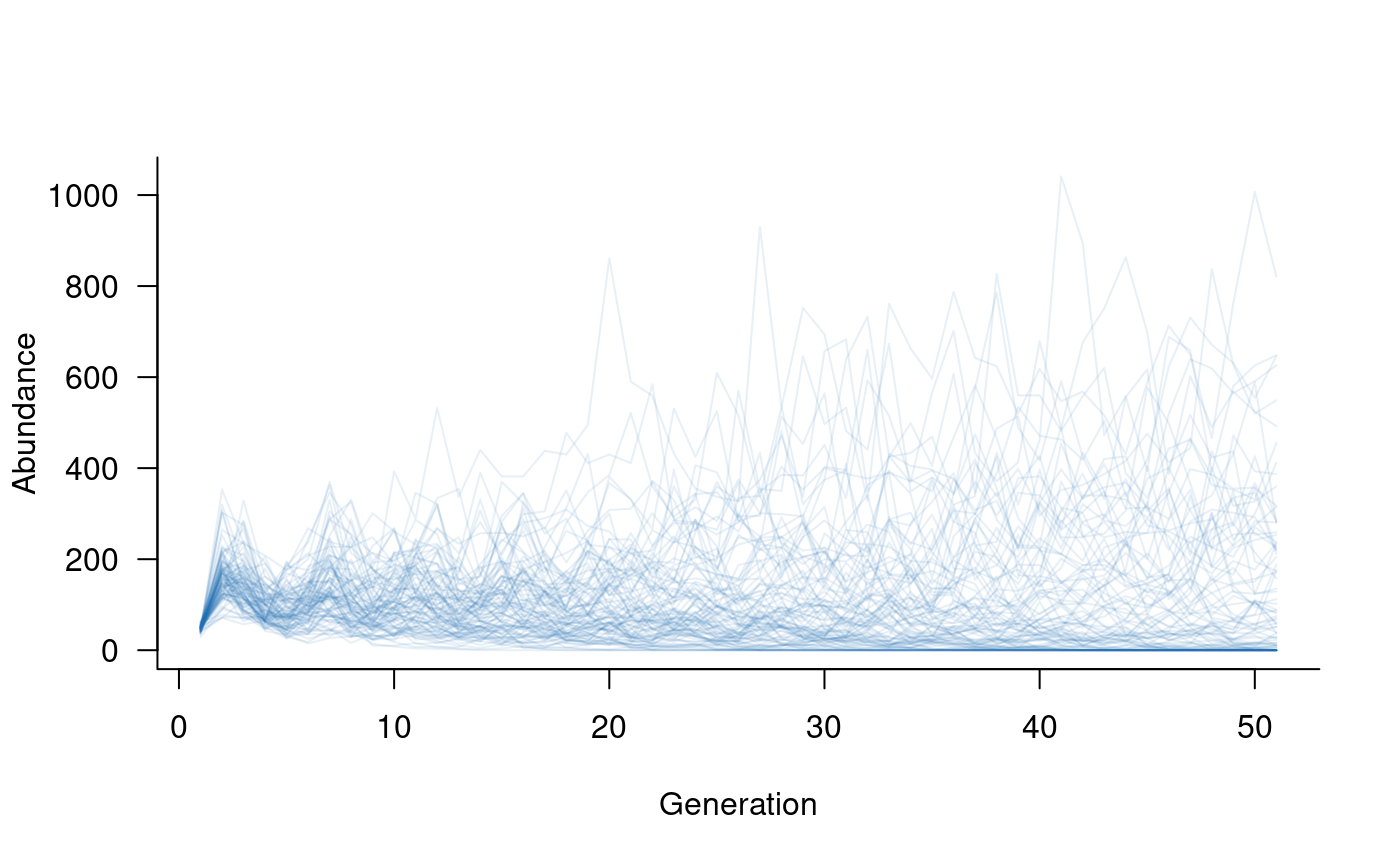

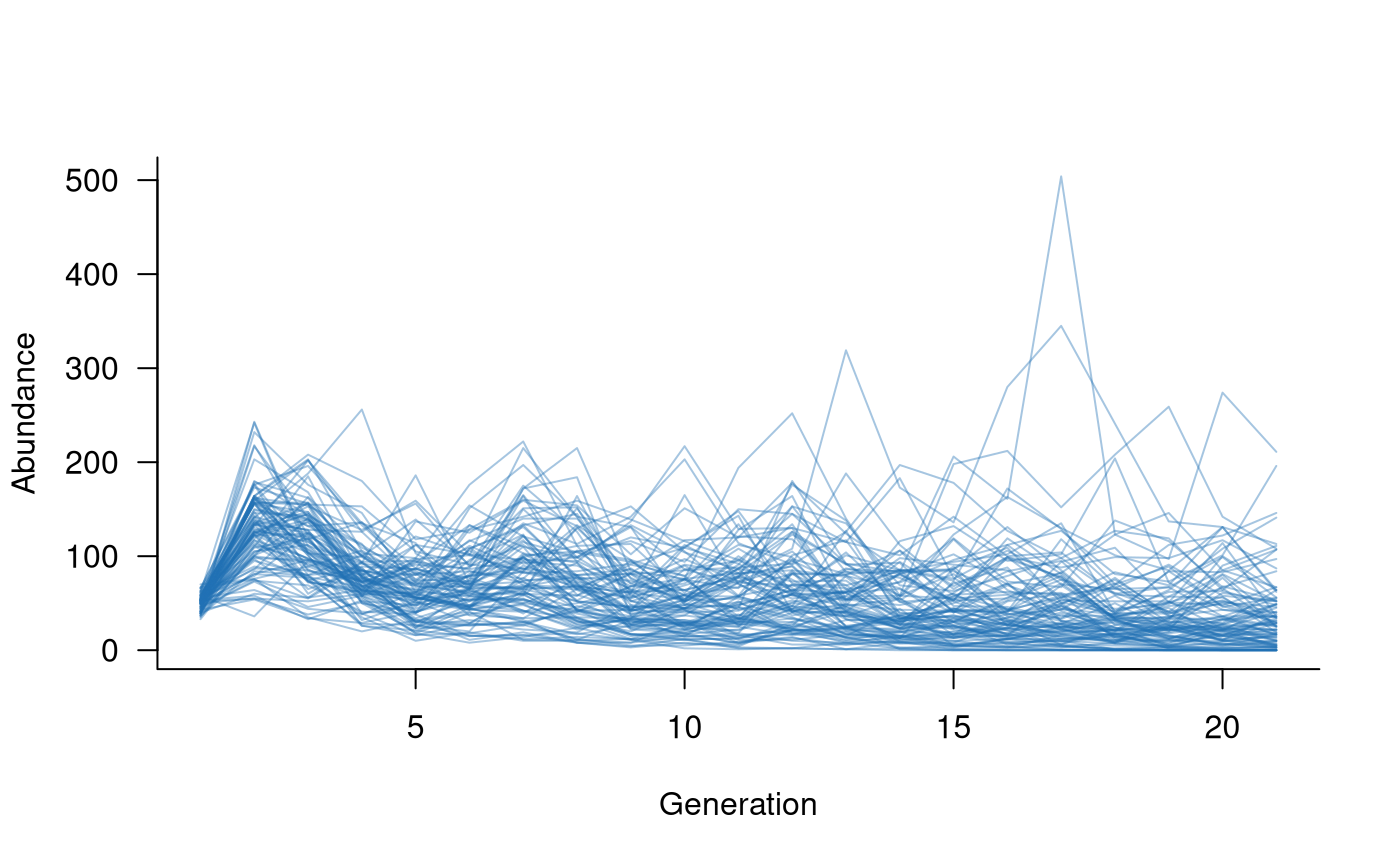

# specify density dependence that removes 10 % of adults in each generation

dd_n <- add_remove_post(

masks = all_classes(popmat, dims = 3:5), # want to focus on adults

funs = function(n) 0.9 * n # define in-line function to return

# 90 % of adult population

)

# create a new population dynamics object

popdyn <- dynamics(popmat, envstoch, demostoch, dd_n)

# simulate population dynamics

sims <- simulate(popdyn, nsim = 100)

# plot the population trajectories

plot(sims, col = alpha("#2171B5", 0.4))

Covariates

Population dynamics often depend on external factors

(covariates, here). aae.pop uses the

mask/function approach described above to

include the effects of covariates on vital rates. The

function takes the vital rates as the first argument,

followed by any arguments required to specify covariate values or their

effects. An example illustrates this most clearly:

# set up 20 years of covariates, such as proportion of available nesting sites

nesting <- runif(20, min = 0.5, max = 1.0) # 50 % to 100 % of total sites available in each year

# define the mask

covar_mask <- reproduction(popmat, dims = 3:5) # assume nesting sites only affect reproduction

# define a function that links vital rates to the covariates

# (dots to soak up any extra arguments passed to other functions)

covar_fn <- function(x, nests, ...) {

x * nests # really simple function, assume the proportion of successful reproduction

# attempts is equal to the proportion of nests

}

# combine this into a covariates term

covs <- covariates(covar_mask, covar_fn)

# create population dynamics object (without density dependence)

popdyn <- dynamics(popmat, envstoch, demostoch, covs)

# simulate population dynamics

sims <- simulate(

popdyn,

nsim = 100,

args = list(covariates = format_covariates(nesting))

)

# plot the population trajectories

plot(sims, col = alpha("#2171B5", 0.4))

Specifying a covariates term does not automatically

include covariates in the model. Note that the nesting

variable also had to be passed to simulate via the

args argument. The reason for this is that it allows a

single population dynamics object (popdyn, above) to be

used with multiple different sets of covariates, without re-compiling

the dynamics object each time.

The format_covariates function is included to format

covariate values into a list with one element per time step. These

formatted covariates can be combined with static covariates by collating

everything into a super-list:

sims <- simulate(

popdyn,

nsim = 100,

args = list(

covariates = c(

format_covariates(nesting),

list(static_argument1 = 0.05),

list(static_argument2 = 100)

)

)

)aae.pop assumes that at least one argument to

covariates changes through time, so a consequence of

specifying covariates is that the vector/matrix of covariates determines

the number of simulated time steps (n_time). In the above

example, there were 20 values of nesting, which translates

to 21 time steps (initial condition plus 20 updates).

It is assumed that covariates will be passed as a list with one

element for each time step. More complex covariate terms

are possible, such as a combination of static and dynamic arguments or

functions that specify arguments based on the current state of the

population. These terms can be passed to simulate via the

args argument (see help files for

format_covariates for examples).

Fine-grained control of covariate effects

Simulated populations can include The default covariates

terms are applied consistently to all replicate trajectories. In some

cases, it may be useful to specify covariate effects specific to each

trajectory. The replicated_covariates process is included

to address this situation, and allows covariate functions to act on the

full vector of vital rates with replicate-specific arguments and

effects.

The simplest way to set up (and visualise) a

replicated_covariates term is to define a matrix with

nsim columns and ntime rows. Each column in

this matrix specifies the covariate values/arguments applied to a single

replicate trajectory, and each row specifies the effects (for all

replicates) at a single time step.

One application of replicated_covariates (and the reason

this approach was developed) is to allow both variation and uncertainty

in vital rates in a single simulation. With this structure, the input

matrix can be defined with variation (e.g., representing environmental

variability) around different mean values (representing uncertainty),

without having to run multiple simulations.

# set up 20 years of covariates, such as proportion of available nesting sites,

# but now with a different minimum (and, therefore, mean) value for each replicate

nesting <- do.call(cbind, lapply(runif(100, min = 0.5, max = 0.8), \(x) runif(20, min = x, max = 1.0)))

# define the mask

covar_mask <- reproduction(popmat, dims = 3:5) # assume nesting sites only affect reproduction

# define a function that links vital rates to the covariates

# (dots to soak up any extra arguments passed to other functions)

covar_fn <- function(x, nests, ...) {

x * nests # really simple function, assume the proportion of successful reproduction

# attempts is equal to the proportion of nests

}

# combine this into a covariates term

covs <- replicated_covariates(covar_mask, covar_fn)

# create population dynamics object (without density dependence)

popdyn <- dynamics(popmat, envstoch, demostoch, covs)

# simulate population dynamics

sims <- simulate(

popdyn,

nsim = 100,

args = list(replicated_covariates = format_covariates(nesting))

)

# plot the population trajectories

plot(sims, col = alpha("#2171B5", 0.4))

Adding or removing individuals from a population

Many processes might lead to individuals being added to or removed

from a population. The add_remove_pre and

add_remove_post functions are defined generically to

capture any such process, with the pre version being

applied prior to reproduction and the post version applied

following reproduction. Similar to demographic stochasticity, additions

and removals act on the population state vector (the counts in each

class) rather than the population matrix (the vital rates). Importantly,

add_remove_pre is the only way in which the state vector

can be modified before reproduction.

Examples of additions include fish stocking and releases of captive-bred individuals. Examples of removals include angling or predation of individuals, noting that both could also be applied as covariates acting on survival rates. A simple example can illustrate the general approach.

# set up a release of 10 individuals each year into the first age class,

# occurring after reproduction

captives <- add_remove_post(

masks = all_classes(popmat, dims = 1),

funs = \(x) x + 10

)

# repeat to remove 2 adults via predation each year, prior to reproduction

predators <- add_remove_pre(

masks = all_classes(popmat, dims = ncol(popmat)),

funs = \(x) ifelse(x >= 2, x - 2, 0)

)

# create population dynamics object (without density dependence)

popdyn <- dynamics(popmat, envstoch, demostoch, captives, predators)

# simulate population dynamics

sims <- simulate(

popdyn,

nsim = 100

)

# plot the population trajectories

plot(sims, col = alpha("#2171B5", 0.4))

What if I don’t want to use masks?

The mask/function approach is central to

aae.pop. This approach allows multiple functions to be

combined into a single term and makes it easier to keep track of (and

update) individual functions or masks. A secondary reason for this

approach is computational. Rarely will any demographic processes act on

the entire population matrix. When dealing with large matrices (e.g.,

50-100 classes), it’s much more efficient to pass small parts of the

matrix than the entire matrix.

There might be situations where the entire population matrix does

need to be modified by a given process. This is still supported in

aae.pop through the all_cells

mask. However, it isn’t possible to subset the matrix

within a function using R’s standard [i, j]

notation. This is because the functions within aae.pop

receive a flattened (and masked) version of the population matrix, which

actually looks like:

# reproduction mask

popmat[reproduction(popmat, dims = 3:5)]## [1] 2 4 7or

# transition mask

popmat[transition(popmat)]## [1] 0.25 0.45 0.70 0.85or

# all elements

popmat[all_cells(popmat)]## [1] 0.00 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.45 0.00 0.00 2.00 0.00 0.00 0.70 0.00

## [16] 4.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.85 7.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00If it’s essential to use [i, j] subsetting inside a

function, a workaround is to reconstruct the matrix within the function

by passing the dimensions through the args argument in

simulate. This might look a bit like:

# define a function

no_mask_fn <- function(x, dim) {

# reconstruct matrix

x <- array(x, dim = dim)

# change elements with [i, j] notation

x[2, 1] <- 0.6 * x[2, 1]

x[3, 2] <- 1.25 * x[3, 2]

# return

x

}

# set this up as a form of environmental stochasticity

envstoch <- environmental_stochasticity(

masks = all_cells(popmat), # pass the entire matrix

funs = no_mask_fn # use the no-mask function

)

# create population dynamics object (without density dependence)

popdyn <- dynamics(popmat, envstoch)

# simulate population dynamics

sims <- simulate(

popdyn,

nsim = 100,

args = list(environmental_stochasticity = list(dim = dim(popmat)))

)

# plot the population trajectories

plot(sims, col = alpha("#2171B5", 0.4))